Breaking out of secured Python environments

A week or so ago I was browsing /r/Python and I saw a link to a website called rise4fun.com, which is a Microsoft Research project that contains a lot of cool demos and tools that you can run in your browser. The demo I was linked to was a restricted Python shell that could be used to experiment with a “high performance theorem prover” called Z3. Python is a highly dynamic language and so it is pretty hard to secure correctly, and I found numerous ways around the restrictions they put in place which I have detailed in this post. Due to these issues the z3py section was removed shortly after I made contact so you can’t see it for yourself, however the plain z3 section is still there so take a look here for reference (just imagine it took Python code as input).

The restrictions

The first thing I did was to explore what restrictions they had in place to prevent malicious activity. I found they had the following restrictions on code being executed:

- Any use of the import statement

- Use of any attribute prefixed with a double underscore (which rules out all Python special methods like __getattr__)

- Use of any attribute name in a blacklist (open, getattr, setattr, locals, globals etc)

They implemented these restrictions by parsing the Python code into an AST representation and looking for any attribute access prefixed with a double underscore, any use of the import statement or any name in a blacklist.

Breaking out

In Python exception’s have a defined hierarchy. The following code is a common way to catch all exceptions while executing some_func():

try:

some_func()

except Exception:

passThis works in most cases as almost all exceptions have Exception as a parent somewhere. However there are a few (MemoryError for one) that inherit only from BaseException and not Exception, and so would not get caught by that code.

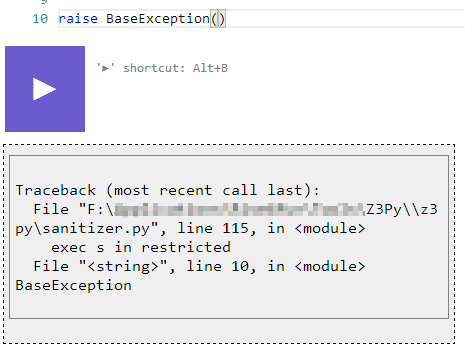

Raising a BaseException() escaped the try/except block they had in place and gave me a nice traceback with some the path to the executing script.

Enumerating attributes

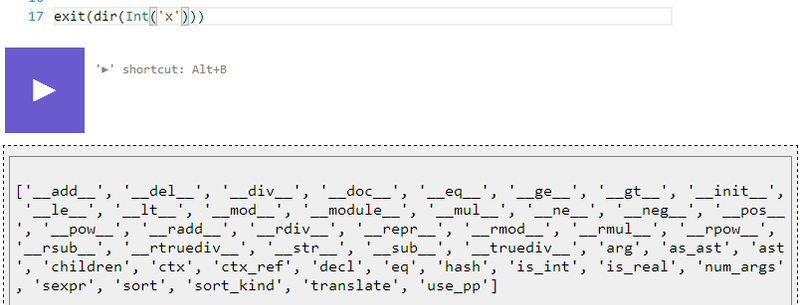

There are a few ways to enumerate attributes in Python, you could use the __dict__ attribute on any class but this was obviously restricted. The other more common way is to use the dir() function, which was not restricted. I found that “print dir(x)” didn’t work and returned no output, however “print exit(dir(x))” did (str was restricted, but exit() turns its parameters into a string):

Accessing restricted functions

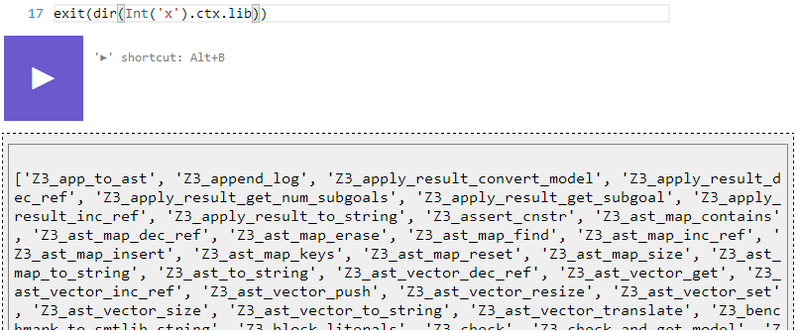

By enumerating the attributes I found an interesting one called “ctx”. This wasn’t interesting by itself, but it had an attribute called “lib” that was a reference to the z3 module, which had some interesting sounding functions.

Writing files

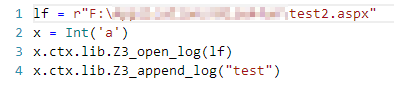

The one that stood out in the z3 module were the logfile functions, Z3_open_log and Z3_append_log. This allowed me a simple way to write files, helped in part by the path I acquired using the BaseException method above:

And the resulting file:

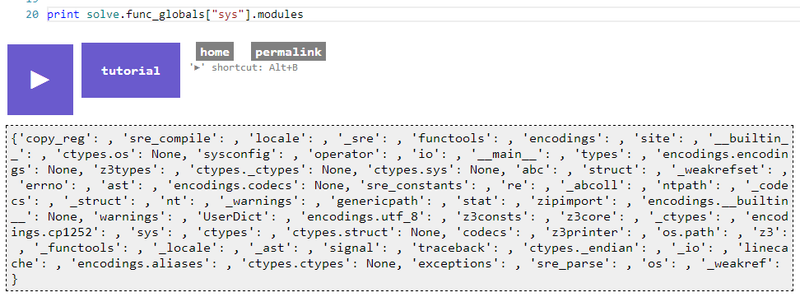

Getting a reference to the sys module

The sys module in Python is a goldmine, if you can get a reference to that in a restricted environment then you will be able to get a reference to any imported module by using the sys.modules dictionary. After a while of getting nowhere I hit myself, I forgot about func_globals. Any Python function has an attribute called func_globals which according to the Python docs is a “reference to the dictionary that holds the function’s global variables — the global namespace of the module in which the function was defined”. Using this we could easily get a reference to the sys module and therefore any imported module:

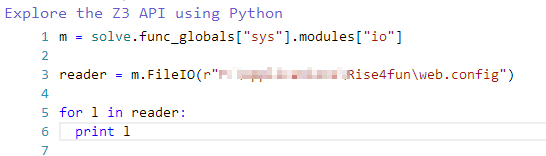

And then we could use the io module to read and write arbitrary files:

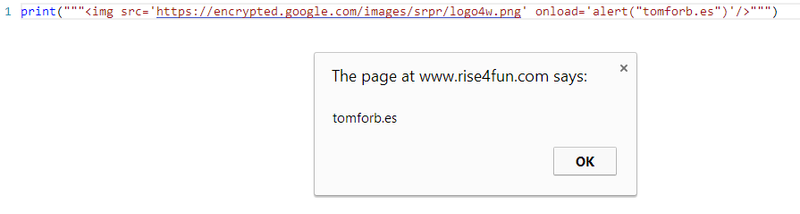

Bonus marks

None of the output was escaped, and while it’s not too serious as there are no user accounts (as far as I know) and so nothing to steal it’s still a bit funny:

Securing Python

Python is hard to secure. The best way is to execute it in a temporary environment (like a temporary docker instance) so that if someone did manage to escape they would not be able to wreak havoc on anything important. That being said the blacklist AST parsing method that rise4fun used was clever and worked to a degree, improvements could be made to make it more viable.